Staying Neutral

How Our History Teachers Navigate Politics in the Classroom

February 14, 2023

An unbiased perspective is hard to come by these days. If you followed the results of the November midterm elections, you likely saw how divided the nation has become on issues across the political spectrum. Party affiliation is our crest, news headlines our warcry, and social media our battlefield, torn by argument and belief.

We as a student body have grown up submerged in this age of media access and political division. Our teachers, who are as new to the age as we are, work overtime to de thread this political climate into tangible lessons about our past, present, and future. Neutrality, they all agree, is crucial to ensure that students remain open to the teachings of history and modern politics.

Katie Saylor, who teaches AP U.S. History, says that teaching history today can feel “like navigating a minefield.” Even efforts to present topics from multiple perspectives, to reduce the chances of one opinion shining through, can give the impression of bias.

Jim McGinnis feels the same tension. He teaches honors American History and Florida History, and he says he has to be careful when the realm of politics seeps into his lectures. Earlier in his career, “I would say things just to be provocative,” hoping to trigger student interest and discussion, he said. “Today, that’s dangerous. If I say something about the president or something about the governor, you just don’t know what the kickback is going to be.”

All teachers agree on the importance of covering as many aspects of the American experience as possible and showing their interconnection. “If you can see how you are influenced by others, I believe that is a real force of tolerance,” McGinnis said. Marc Bailey, who teaches honors American Government and spent many years teaching junior high American History, agrees: “If you have a knowledge deficit, you’re making judgements,” he said. The first step to reaching an understanding is therefore to “get informed.”

The path to covering the entire bedrock of American culture isn’t easy. And eliminating the semblance of bias in the process is even more difficult, especially when teaching about the more uncomfortable foundations of our nation. For instance, racial equality critics have advocated for years for a more diverse retelling of American history, calling out textbooks for whitewashing our nation’s past.

Other critics of the state of today’s history education, like Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, fear the emotional consequences of detailing the past that instill contrasting senses of “privilege” or “oppression” in students—as quoted from the recently passed “Stop W.O.K.E.” Act, which aims to prevent divisive ways of portraying racial, feminist, and queer history from entering the classroom.

Teachers find navigating this heated environment to be difficult. “The challenge for me,” Saylor said, “has been in the last couple years, trying to say things very carefully, bring up a well-rounded history. Teach the facts, teach what happened, teach the realities of history, which are not always pretty and not always wonderful. At the same time, staying neutral, not trying to push a political agenda of any kind.”

Teaching well-rounded history can necessitate straying from textbook accounts, says Bailey, who feels that these materials can still deliver the wrong message. For instance, they are often missing “a lot of details related to the African American experience,” he said. While the true and horrific nature of slavery and other patterns of black oppression are growing more widely addressed, Bailey still feels “an absence of a black narrative beyond the institution of slavery,” particularly one spotlighting the historical accomplishments of African Americans.

Teaching only one side of history, especially one that depicts only oppression without highlighting the achievements of those fighting and rising above it, neglects another important role that history teachers fill: the source of empowerment. “These stories have to be told in a better light,” he said. As a history teacher, “I’m going to deal with the absence of how much women should be esteemed. I’m going to deal with the absence of how much blacks have overcome in this country.” He feels the obligation to teach “in a way that’s empowering and informative” to provide “a complete and total narrative of what American history looks like.”

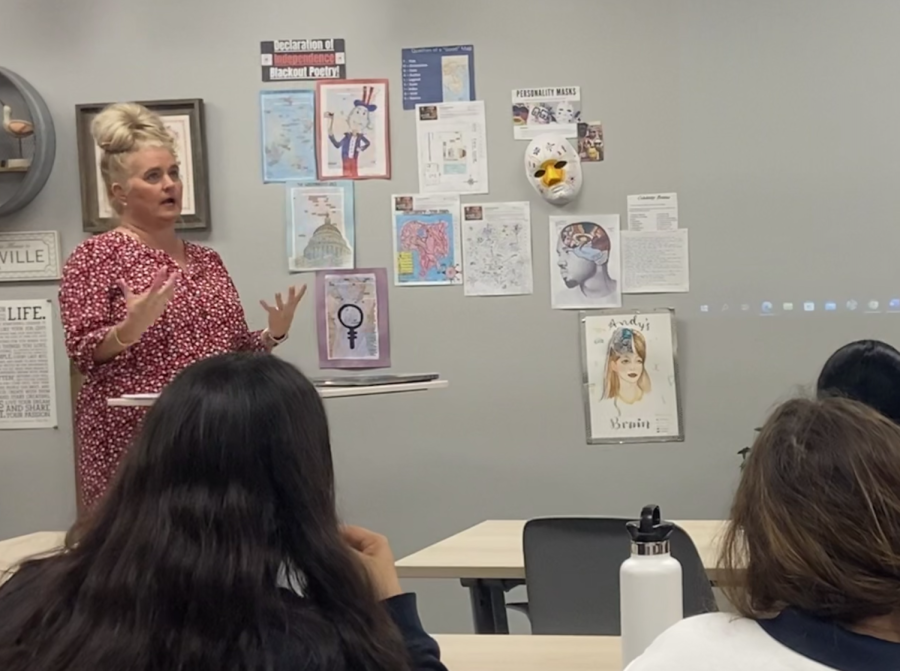

How students process this objective narrative is another opportunity for academic guidance. Lisa Dykes, who teaches a variety of social science classes at HT, including AP U.S. Government and Politics, emphasizes critical thinking, the ability to deeply question and analyze new information. By remaining neutral, she can show students how to approach novel ideas without bias. “My class… is not a place where ideology is pushed as a way of influencing,” she said. “It’s not my job as a teacher to teach people what to think. It’s how to think.”

But as more topics are stigmatized for being too political, revealing bias as an educator has grown difficult to prevent. It can feel like “walking on eggshells,” McGinnis said. The danger lies in distinguishing fact, opinion, and belief: three things that are often confused by young citizens who are just beginning to understand the complicated history and present political climate of our country. This confusion can result in an emotional fragility that is difficult to cushion when one depiction of the same historical event can feel like a personal assault and another like patriotic validation.

The ability to accept new information, however, is fundamental to the human experience, McGinnis believes. “Changing your mind is not an act of weakness,” he said. When Dykes implores students to question their own political beliefs, to “dive deep and start peeling back the layers,” she finds that “students realize they’re not exactly who they thought they were, and it makes them argue a little differently,” she said. Perspective metamorphosis builds empathy, the ability to understand the mindsets and relate to the circumstances of others.

Bailey believes similarly: understanding history takes an “emotional maturity” that is cultivated over time. Understanding history means understanding the “intrinsic motivation” of historical figures like George Washington, Sojourner Truth, and Clara Barton, he says. With this understanding, students can more easily understand the motivations of people today. Ultimately, “I want my students to be able to have an intelligent conversation with anyone of any race, of any gender,” he said.

Perhaps more importantly, students must learn “how to disagree with people in a civil way,” Saylor said. “I think that’s a huge problem in American discourse right now. We attribute emotions to people instead of just discussing the argument at hand.”

Holding an educated conversation today requires multiple faculties—a knowledge of the subject; an awareness of personal bias; a respect for others’ vulnerability; and a willingness to shift all understandings at the introduction of new, trustworthy information.

History teachers are given the heavy task of honing these abilities in their students to ease their political-emotional insecurity. As Saylor began, “At the end of the day, everyone’s entitled to their beliefs and everyone’s entitled to their opinions.” As Dykes concluded, “There’s nothing wrong with having an opinion. You’re just not allowed to weaponize it.”